By Ashlynn larsen

“In a time where it feels like everyone is an “Expert” I hope you know how valuable it is to say, I don’t know and I am still learning”

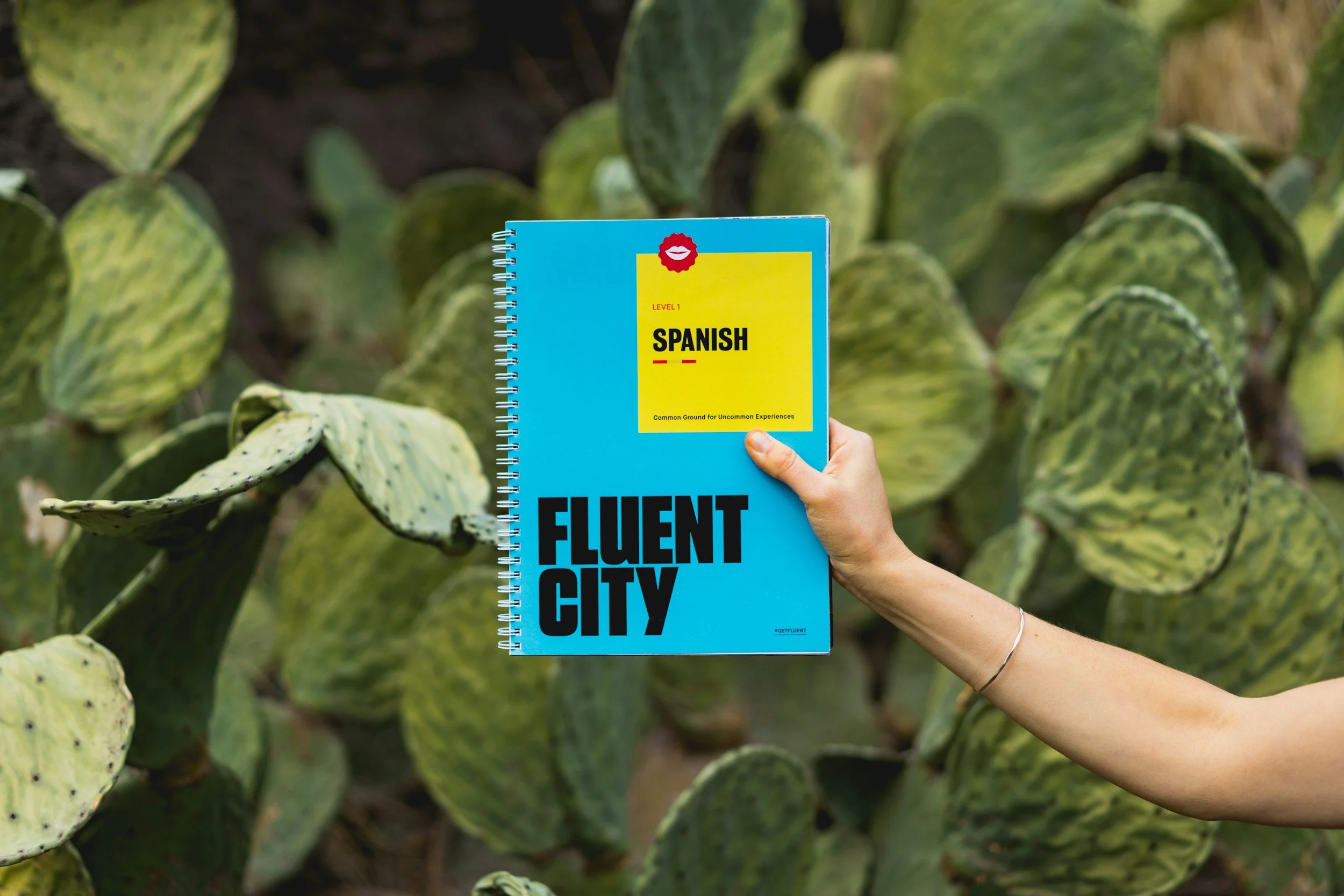

For my fall semester of school, I decided to challenge myself by taking a new language class. As I walked in, excitement soon turned into anxiety. I was the only person with no prior experience in the language, and it felt as if everyone else had already mastered the basics. I stumbled through simple phrases, unsure of myself, while others seemed far more confident. It was hard. There is a part of me that wants to hide or give up, but I am realizing something powerful in the process: there is bravery in being a beginner. It requires strength to admit that I don’t know something and even more courage to embrace the learning process.

The Bravery to Be a Beginner

Being a beginner is often uncomfortable because it taps into a deep-seated fear of failure and inadequacy. For me, sitting in that language class, fumbling over grammar rules, and feeling far behind, was deeply humbling. But research shows that being new at something, and even failing along the way, is crucial to our development. Psychological flexibility, or the ability to adapt to new situations and accept challenges without fear of failure, is essential for growth.

Kashdan and Rottenberg (2010) define psychological flexibility as the ability to shift perspectives and behaviors in response to changing environments. Their research suggests that those who embrace new experiences with an open mind—especially when they feel out of their depth—tend to exhibit greater resilience and emotional well-being. This aligns with my experience in the language class. By pushing through the discomfort, I found that I grew not just in my language skills but also in my capacity to handle difficult, unfamiliar situations.

The Power of a Growth Mindset

What allowed me to persevere in that class wasn’t just grit but a shift in mindset. I began to see mistakes as part of the learning process. This is a core tenet of Carol Dweck’s (2006) growth mindset theory, which suggests that individuals who believe their abilities can be developed through effort are more likely to succeed in the long run. Dweck’s research shows that those who view failure as an opportunity to grow are more likely to persist in difficult tasks.

More recent studies support this. Yeager et al. (2019) found that students who were encouraged to adopt a growth mindset showed reduced anxiety and improved performance. They were more likely to view challenges as opportunities for learning rather than as threats to their self-worth. In my language class, shifting my mindset from “I’m terrible at this” to “I’m learning” transformed my experience. Each mistake became a stepping stone rather than a stumbling block.

The Lost Art of Enjoying What We Do

As I have been navigating the discomfort of being a beginner, I noticed a cultural shift in how we talk about our hobbies and passions. When meeting new people, I realized that many of us only share hobbies we’ve mastered. Instead of talking about what brings us joy, we tend to default to the activities we are good at. This reflects a broader societal trend where we equate self-worth with expertise.

Flett et al. (2016) describe this phenomenon as a form of socially prescribed perfectionism, where individuals feel pressured to appear competent in all areas of their lives. This pressure often leads to stress, burnout, and a reluctance to engage in activities purely for enjoyment. I’ve caught myself doing this, too—when asked about my hobbies, I’m hesitant to mention things I enjoy but am not yet skilled at. But why should mastery define whether we can pursue or share our interests?

This reluctance to embrace what we’re still learning highlights a lost art—the joy of being a beginner. Studies suggest that pursuing activities for intrinsic pleasure, rather than for performance or validation, promotes well-being. In a review by Ryan and Deci (2017), they emphasize that engaging in hobbies and activities for intrinsic enjoyment, rather than external recognition, fosters greater psychological health. By focusing on what we like rather than what we are good at, we give ourselves permission to embrace the learning process without fear of judgment.

Reframing Failure: A Path to Growth

Being a beginner in any endeavor, whether it’s learning a language, picking up a new hobby, or starting a career, involves inevitable mistakes. This can feel discouraging, but research shows that how we interpret failure is key to how we move forward. In a study by Fischer, Pauw, and Karremans (2021), participants who were encouraged to view their failures as part of the learning process were more persistent and performed better on challenging tasks than those who saw failure as something to be avoided.

For me, this has been crucial in my journey of learning a new language. Every misstep—whether it’s forgetting a word or mispronouncing something—used to feel like evidence that I wasn’t cut out for this. But by reframing these mistakes as opportunities to improve, I started to see the beauty in the struggle. This shift in perspective didn’t just help me in language class; it’s a lesson that applies to all areas of life.

The Role of Psychological Safety

Being brave enough to admit that we’re just learning not only benefits us individually but can also create environments where others feel safe doing the same. When I started admitting to my classmates that I was struggling, I noticed they became more open about their own difficulties. Research supports this. Psychological safety—the belief that one can take risks and make mistakes without fear of negative consequences—has been shown to enhance learning, collaboration, and performance in groups (Edmondson, 2019).

Brown’s (2012) research on vulnerability also highlights this point. When we allow ourselves to be seen as imperfect, we invite others to do the same, fostering deeper connections and greater collective resilience. This was evident in my language class, where being open about my beginner status not only helped me feel less alone but also created a more supportive learning environment for everyone.

Embracing Uncertainty: The Courage to Move Forward

The fear of the unknown is often what holds us back from trying new things. Whether it’s learning a new skill, starting a new job, or stepping into unfamiliar territory, uncertainty can be paralyzing. But research suggests that those who can tolerate uncertainty tend to be more resilient and experience less anxiety. Hirsh, Mar, and Peterson (2012) found that individuals who are more comfortable with uncertainty are better equipped to handle stress and are more likely to engage in exploratory behavior.

In my own experience, learning to cope with the uncertainty of mastering a new language has been challenging but rewarding. The more I embrace the idea that I won’t always know the right answer, the more I open myself up to growth. This mindset has allowed me to approach other areas of life with greater curiosity and less fear.

The Bravery to Keep Learning

Saying “I’m just learning” is not a sign of weakness—it’s a testament to bravery. It allows us to shed the need for perfection and focus on growth. My experience in the language class has taught me that there’s immense power in being a beginner. It’s not just about learning a new skill—it’s about developing the resilience to face challenges head-on, to embrace failure, and to keep moving forward.

We live in a world where expertise is often prized above all else, but there’s something deeply valuable about the journey of learning. The next time someone asks me about my hobbies, I might just tell them that I’m learning photography, and that’s okay. Because enjoying the process of learning—without the pressure to be an expert—is what true growth is all about.

“You don’t have to be great to start, but you have to start to be great.”

References

Brown, B. (2012). Daring greatly: How the courage to be vulnerable transforms the way we live, love, parent, and lead. Gotham Books.

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

Edmondson, A. C. (2019). The fearless organization: Creating psychological safety in the workplace for learning, innovation, and growth. Wiley.

Fischer, A. H., Pauw, J. M., & Karremans, J. C. (2021). The benefits of reframing failure: How failure reframing can promote persistence and performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 93, 104081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2021.104081

Flett, G. L., Nepon, T., Hewitt, P. L., & Zaki-Azat, J. (2016). Perfectionism, social disconnection, and interpersonal consequences: Implications for interpersonal acceptance and close relationships. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 8(3), 343-360. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.121 47

Hirsh, J. B., Mar, R. A., & Peterson, J. B. (2012). Psychological entropy: A framework for understanding uncertainty-related anxiety. Psychological Review, 119(2), 304-320. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026767

Kashdan, T. B., & Rottenberg, J. (2010). Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(7), 865-878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.001

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Yale University Press.

Yeager, D. S., Dweck, C. S., Walton, G. M., & Cohen,