“When we seek for connection we restore the world to wholeness. Our seemingly separate lives become meaningful as we discover how truly necessary we are to each other.”

Supportive Relationships: A Fundamental Human Need

Why would relationships have such an impact on our health and happiness? A wealth of evidence suggests that our needs for social connection are deeply rooted in human nature. Our early ancestors sought the companionship of others for warmth and security, greater access to resources, protection from predators, and, of course, procreation. Those who were well connected were more likely to survive and pass on their genes than isolated individuals. Thus, evolution naturally selected social behavior over nonsocial behavior because it promoted humans' ability to survive and reproduce.

Wired for Connection

Our natural affiliation for social connection is apparent in our biology. Through the use of fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) studies, neuroscientists have discovered key areas in the brain involved in various social processes. [If you’re not familiar with fMRI procedures, click here to watch a short explanation video]. These brain regions have evolved to motivate us to create and maintain social bonds, resist their dissolution, and to think about and understand the minds of others (Lieberman, 2013).

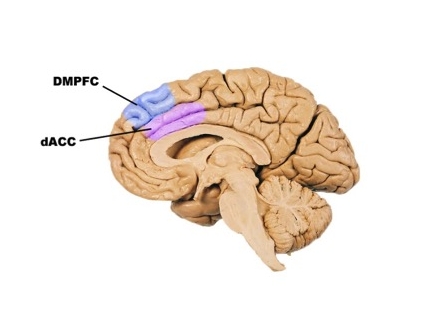

One of these regions is the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC), highlighted in purple below. This brain region is responsible for producing the emotional distress we feel in reaction to pain. Interestingly, the dACC responds to physical and social pain almost identically. This means that whether you are feeling rejected or you have an achy back, your brain processes both events as important threats that should be attended to. Interestingly, researchers have found that taking acetaminophen (Tylenol) actually helps reduce the social pain we feel. In a study by DeWall et al. (2010), one group was given a placebo to take for three weeks, while the other group was given Tylenol. None of the participants knew which pill they were taking, and still, those who took Tylenol reported feeling significantly less social pain than the placebo group. This study and others like it help us understand just how real social pain is, and perhaps encourage us to take a kinder and more sympathetic approach to those who are experiencing social pain. The dACC prompts us to stay connected by producing emotional distress when we feel threats to our relationships.

Another brain region responsible for social processes is the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (DMPFC), highlighted in blue above. This brain region is responsible for mentalizing—-that is, thinking about others' thoughts, beliefs, goals, desires, and intentions. The ability to think about and understand the mental states of others is unique to primates, and it allows us to predict how a person may respond to a situation and to interact with them more effectively. Mentalizing is so basic to our nature; you do it all the time without even realizing it!

Interestingly, the DMPFC is also active during periods of rest from a cognitive task. Why would that be? Could the people sitting in the scanner be purposely thinking about their significant others, kids, spouses, or coworkers when they weren’t performing a task? Dr. Lieberman (2013) (one of the world’s leading researchers in social cognitive neuroscience) suggests that this mentalizing network comes on automatically, as if by default so that our brains can practice being social and help us prepare for social encounters. In fact, when he tested this hypothesis in the lab, he found that participants who had high mentalizing/default network activity in the seconds right before a mentalizing task performed significantly better than those who showed less default network activity. It’s clear that the DMPFC plays a crucial role in our ability to connect with others and to understand their hopes, fears, goals, and intentions.

The social functions of the dACC and the DMPFC are evidence of our inherent social nature. If you are interested in learning more about the social brain, check out Dr. Lieberman’s book, Social: Why Our Brains are Wired to Connect.

The Need to Belong

Not only are we wired to connect, but the inner drive to create social bonds is actually a fundamental need, and it influences our thoughts, feelings, and behavior. From the moment children are born, they need someone to care for them and provide for their physical needs to survive (Bowbly, 1988). Infants can develop strong attachments to their caregivers very easily, and become distressed when they are left alone. This attachment system is inherent in all of us and it lasts a lifetime. Just as infants become distressed and cry when they are separated from their caregivers, we too experience social pain and may behave rashly when we perceive threats to our relationships. Dr. Lieberman (2013) explains that because we have this inherent need to belong, “...we never get past the pain of social rejection and we always have an intense need for social connection and to be liked and loved just as an infant needs to be connected to a caregiver.”

As authors and positive psychologists define it, belonging is a feeling of mutual love and value, and frequent pleasant interactions with people (Smith, 2017). For decades, early theorists have recognized this fundamental need to belong. More than 50 years ago Abraham Maslow theorized that the need for love and belonging came right after basic needs such as food, water, and safety, but before the needs of accomplishment and achievement (see Maslow’s hierarchy represented below).

https://www.simplypsychology.org/maslow.html

However, many psychologists today argue that Maslow had it wrong, and that the need to belong should actually be at the bottom of the pyramid right next to the need for food and water. Is our need to belong so vital that we need connection just as badly as we need water and air? What do you think? In 1945, a researcher named Rene Spitz published a revolutionary study that suggested an answer this very question. Spitz compared the health of two groups of infants—those living in solitary confinement in an orphanage, and those attending a chaotic nursery in a prison where their mothers were incarcerated. While the infants living in the orphanage were better protected from germs and diseases, the infants attending nursery at the prison were able to play and interact with each other and their mothers. Spitz found that by the end of his study 23 out of 88 children in the orphanage had died, compared to none of the children in the prison nursery. He argued that the orphan children were suffering from a lack of love; that they didn’t feel a sense of belonging or nurturing. This is compelling evidence for the argument that the need to belong may be just as fundamental as the need for physical nourishment.

Baumeister & Leary (1995) further argued that the desire for interpersonal relationships is a basic, innate human motivation. They presented several evidence-based claims as support. Here are a few of them:

People of all cultures form groups fairly easily. People form bonds in adverse circumstances and even when they are placed in groups with people they don’t know.

All people resist the dissolution of relationships and are distressed when they end. Some even continue to send Christmas cards to people they never talk to because they don’t want the relationship to end!

People think about events in the context of their relationships.

People experience positive emotions when they form social bonds and negative emotions when those relationships are dissolved.

People who lack interpersonal relationships show adverse health effects.

It is clear that the need to belong is a fundamental part of human nature, and when this need goes unmet, our mental and physical health suffers. So the next time your ex sends you a nasty text, or your spouse gets mad at you for coming home too late, just consider why they are acting that way—they may be feeling the pain of social rejection! Every person has an attachment system and a natural desire to feel loved and supported. Unfortunately, many aspects of modern Western culture are often at odds with social connection. In the next section we examine a few important barriers to connection that are increasingly placing our relationships at risk.