Atomic Habits

“We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit.”

In Atomic Habits, author James Clear (2018) explains the power of small, everyday habits that change our lives. Atomic refers to one of the smallest units as well as a source of immense power. An accumulation of small habits in someone’s life makes a big difference over time. For example, an improvement of 1% each day may seem small, but over the course of a year, it will result in a complete change, and a decline of 1% each day will leave you at 0. Just as atoms build on top of each other to create something, habits also build on each other. You can have a lot of bad habits build on each other or make a lot of good habits build on each other, the end result should be obvious for either choice. This is similar to the idea of keystone habits we just discussed.

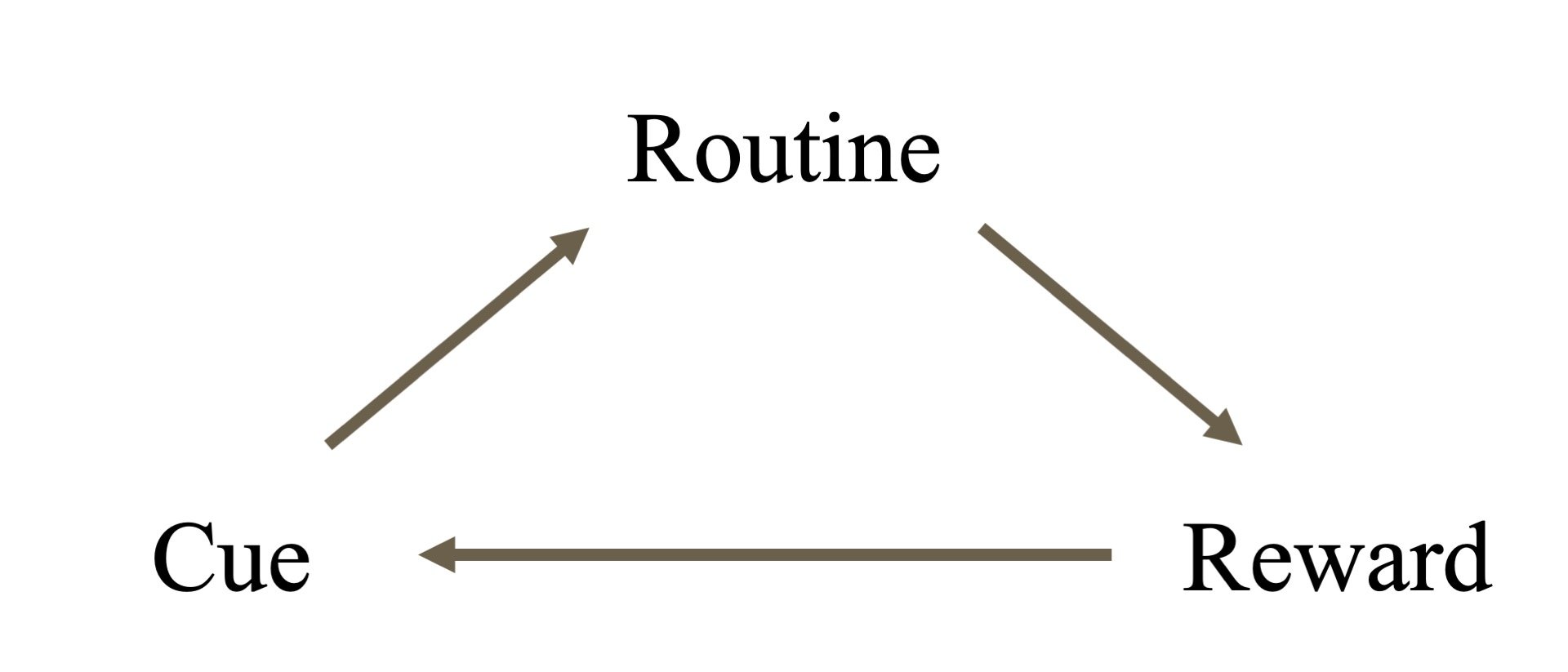

In order to change habits and make new habits, you must be aware of the change you want to make. This includes being aware of what makes up our habits. Clear describes the looping process in the mind as: cue, craving, response, and reward. Cue triggers the action. This might be the smell of cookies in a bakery. Craving pushes people towards doing the habit. You start craving a cookie because you remember how good cookies are! Response is the habit in action, which can be performed physically or mentally. This would be you walking into the store to buy that mouth-watering cookie. Reward is the satisfaction that ceases the craving for a short time until that craving happens again. This would be the taste of that fresh delicious cookie you just ate. You have now just associated this cookie with the place you are at right now. Now, every time you walk past this street and see that bakery, you will want to buy another cookie, and if you do you will make that habit even stronger. However, if you are aware of your cookie monster devouring habit, then you’re one step in the right direction to changing that habit.

James Clear created The Four Laws of Behavior Change in order to build healthy habits and break bad ones. Make it obvious, make it attractive, make it easy, and make it satisfying.

First, make it obvious. The biggest cues for habit are place and time. You can account for place and time through a useful tool called an implementation intention—-how you intend on implementing your plan (habit). The format is as follows: When X happens, I will do Y. In the case of time and place you could say: I will do X, at Y time in Z place. For example, I will workout (x) at 7 am (y) in my living room (z). Another step is to stack your habits on each other. This involves making the last part of your habit become the cue for something else. For example, I will workout at 7 am in my living room. Once I am done working out (cue), I will go shower in my bathroom (next habit). This way you can build good habits on each other to create a routine you desire.

Second, make it attractive. Studies have shown that the anticipation of the reward has almost the same effect as getting a reward. Cocaine addicts and gamblers often have a spike in dopamine right before they are exposed to their addiction (i.e., cocaine and gambling). In order to take advantage of this, use Anticipation Bundling. Associate something you do not want to do with something you do want to do; more probable behaviors can condition less probable behaviors. For example, if you have a habit of procrastinating on Instagram, then commit to working for at least 40 minutes on something you have to do, then indulge yourself with Instagram for 5 minutes. You can even stack this with other habits. For example, after I finish my dinner (habit), I will wash my dishes (desired habit). After I wash my dishes, I will play 15 minutes of video games (reward). You have to commit to yourself that you cannot play any video games until the dishes are done. Another tip that could help is reframing your mindset. Instead of saying you have to do something, say you get to do something. It isn’t, “I have to do homework,” instead it is, “I get to exercise my brain, improve myself, and prepare for my future.” Instead of saying, “I have to go to the gym,” say, “I get to build my endurance, become healthier, and feel better about myself.”

Third, make it easy. The most important step to forming a habit is to just do it (not sponsored by NIKE ;) ). Repetition is crucial. The more times you complete an action, the more likely it will be encoded in your brain. If you make your habit easy, you’ll be more likely to do it which will encode it in your brain faster. Try out the 2-minute rules: when you start a habit it should not take you more than 2 minutes to finish. That means when you first start out with your habit (i.e., read, meditate, or workout) only do it for 2 minutes and not any longer. Once you make something easy to start, the rest will fall into place. For example, go for a run but make sure you only run for 2 minutes. You’ll start to make a habit out of putting on your workout clothes, maybe finding some music to play, and going outside. In reality, this all might take more than 2 minutes but plan on doing your desired habit (running) for 2 minutes, despite prep time (i.e., driving to the gym, changing, etc.). When that habit is established, then you might start to think that you might as well keep running. It might seem ridiculous to drive somewhere only to do something for 2 minutes, but that is part of the process. Also, stop relying on willpower. When your motivation is higher, try using that energy to put things in place that will maximize your chances of following through. Making your cues highly accessible will strengthen and speed up the formation of habits (Hagger, 2019). This is a strategy called environmental reconstructing, changing your physical or social environment in order to promote or avoid a habit (Hagger, 2019). Pack food for the week, set clothes out on your bed for a workout, set out kitchen supplies to be ready to cook. Shape your environment so it is easier to do your habit, like buying black out curtains and moving your tv out of your room to sleep better. Sometimes, all that is needed to form a habit is to start it. The trick is to JUST SHOW UP!

Fourth, make it satisfying. Our minds prioritize instant gratification over long term gratification. What is immediately rewarded is repeated! Many people will choose soda over water for its sugary taste and bubbly mixture. Chapstick can promote lip care with a minty taste. Apply this by rewarding yourself for completing a habit. For example, start a savings account and name it something you want to buy. Let’s say every time you eat at home instead of going out, you put the difference you would have spent into that savings account. If it is easier, you could put 3 dollars into the account every time you eat at home. You will be able to visually see the fruits of your effort. However, you need to be careful that the reward aligns with the habit. If you have a goal to lose a few pounds, you shouldn’t reward yourself with ice cream after every workout.

Here are some additional tips to help you build habits:

Tracking your progress on a calendar is a great way to make your habit obvious, attractive, and satisfying. Streaks on a calendar act as an obvious cue to remind you everyday. When we see progress, we naturally want to feed that progress because we crave achievement, which makes it attractive. It is satisfying to see things grow and feels good to keep a record of success. If you miss a day, it’s ok, no one is perfect. Just make sure you do not miss two days and start a bad habit of missing.

A couple great smartphone apps for establishing and tracking new habits are Productive for iOS or Grow for Android. Make sure to set specific goals for your habit. When forming goals, remember to use S.M.A.R.T. goals and don’t be afraid to revise them as you go (Hagger, 2019; Willmott & Parkinson, 2017). It is found that revisement of goals, repeated success of goals, and positive feedback increases habit consistency (Hagger, 2019; Willmott & Parkinson, 2017).

Just as important as the numbers you record (e.g., time devoted to task, completion percentage) are the reflections and insights you record as you learn along the way. For example, when things seem to be going really well with your growth habit, make a note of what’s working, what you’re learning, and revisit likely future obstacles and what you’ll do when they arise (the last half of the WOOP approach). When you fall short of your intentions, make a note or two on what happened and how you can learn from it. Over time you’ll start to see patterns emerge that will help you make refinements to your growth habit efforts.

You can use the 21-Day Growth Experiment spreadsheet to track your efforts and keep notes on insights and lessons learned. Here it is as an Excel file, or as a Google spreadsheet (to use the Google spreadsheet go to File → Make a Copy, and save a copy for your own use).

Along with the short-term reward, consider the long-term reward and how that may tie in with your values (click to see Values module). Studies show that intrinsic motivation is the most powerful form of motivation (Gardner et al., 2018; Willmott & Parkinson, 2017). When a habit is tied to a core value, it may become intrinsic motivation for you to accomplish it. For example, if regular physical exercise is your target habit, you can regularly remind yourself of your core value of living a healthy lifestyle and set up a reward schedule of buying a new article of clothing for every two weeks of regular exercise (or whatever will motivate you).

Leverage social support. If you can, bring a friend into your growth habit routine. For example, agree with a friend or family member that you will each start a gratitude journal, and share entries on a weekly basis. If possible, find a small group of friends to start one of the 21-Day Growth Experiments together, and make a friendly competition out of the spreadsheet point system! Alternatively, consider whether telling others of your new growth habit intentions will make you feel more motivated to follow through. In addition, be aware that you tend to develop the same kinds of habits as the people you spend time with, so be mindful of the associations you cultivate.

If you want to change something about yourself, you must change what you do. An actor performs, a chef cooks, and an artist paints. People receive their titles because of the things they do. Choose who you want to be. Then everyday as you confront a decision, ask yourself what that type of person would do. It becomes easy to perform an action when it’s a part of who you are rather than what you’d like to do. Small changes over time will result in big changes.

Habit Loop Created By Charles Duhigg