By Ben Anderson

“Souls, in general, are living mirrors or images of the universe of creatures.”

We are living mirrors. Each Earth Day, we are reminded of our connection to nature. However, I would like to tell you about a philosopher who was talking about our interconnectedness with nature all the way back in the 1700’s. He was not the first to do so, but he, to my knowledge, was the first philosopher to make interconnectedness a hallmark of his metaphysical system. This philosopher is one Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, who is famous for his co-creation of calculus as well as his tomes of philosophical and mathematical thoughts and arguments. Allow me to elucidate Leibniz’s thoughts on our interconnectedness with nature, and then illustrate some of the benefits of thinking about ourselves as “living mirrors.”

Check out our Youtube video linked here to hear Einstein’s thoughts!

Imagine you are walking through a crowded city, a bustling burrow, a serene suburb, or any kind of luscious locale. You decide to stop for a second to observe all that’s around you. The sun hits a particular tree or building just right, where it feels like everything was just made for you in that moment. Your doubts go away, your fears subside—maybe for just a second—and everything feels just right. Leibniz talks about this feeling in terms of our connectedness to nature by calling it accommodation. Everything was designed for you at that moment, and you actively contributed to that moment too (1714). Your actions, though you may not know it, contributed to someone else feeling that same awe you felt. As it turns out, every living thing is contributing to that moment of awe you felt. Leibniz believes that we are irrevocably connected to nature.

“Just as the same city viewed from different directions appears entirely different and, as it were, multiplied perspectively, in just the same way it happens that, because of the infinite multitude of simple substances, there are, as it were, just as many different universes, which are, nevertheless, only perspectives on a single one…”

Furthermore, Leibniz believed that everything we do is of great importance. Struggling with a math test? Feeling sad about a recent break-up or rejection? All of our life’s events, big or little, happy or sad, contribute to the, “best possible world,” that Leibniz believes we live in (1710). Even our sadness contributes, in a way we could never understand, to our world, the best one possible. Although Leibniz primarily thought about the best possible world in context of his religious convictions, he believes that the world we are in is the most perfect world due to its activity (1714). Each action we do contributes to a large, infinitely long web of interrelated causes. If we are connected to every living thing, and our actions, whether we know it or not, are of cosmic importance, should that change how we live?

Stepping away from Leibniz, the benefits of feelings interconnected have been demonstrated empirically as well. In a study done by Zhang et al. (2014) they wanted to see how engagement with nature’s beauty predicted feelings of interconnectedness and well-being. They found that those “emotionally attuned to nature's beauty,” had greater levels of well-being when they felt connected with nature. Howell et al. (2011) recorded similar results. They found that interconnectedness with nature strongly correlated with one’s well-being and mindfulness. Altogether, these results suggest that we are more likely to have greater well-being and mindfulness as we engage with nature and feel its beauty (Howell et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2014).

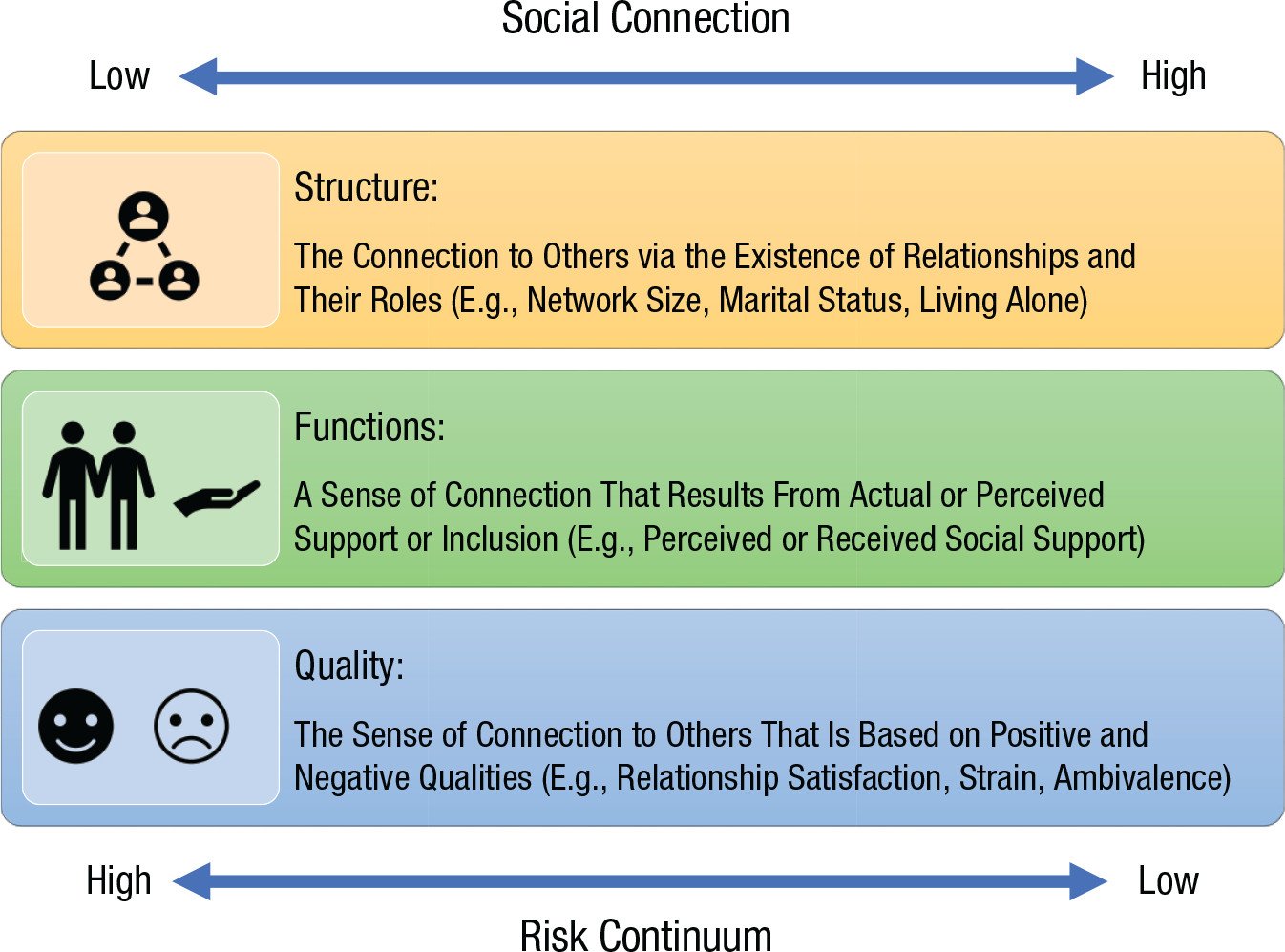

As living mirrors, we can benefit from and find joy and well-being in connecting with the world around us; however, let us also remember to connect with the people around us. Research done by Dr. Holt-Lunstad, a friend of the blog and researcher at BYU, has illustrated that social connection is vitally important for our health. In her article, “The Major Health Implications of Social Connection,” she summarizes many of her and her colleagues’ findings. Dr. Holt-Lunstad (2021) explains that feeling disconnected from others presents, “serious long-term consequences, including earlier death.” Social connection is vital for our health, and thus we need to connect with others. The picture below, taken from the article, summarizes it well:

If you truly want to maximize the benefits of interconnection, why not combine the environment with our social connection? Feel both connected to nature while being socially connected with those close to you. Maybe go on a hike with your friends? Volunteer for a local river cleanup? What you do doesn’t have to be big, it can be quite small. Remember, Leibniz believes that ALL we do, big or small, contributes to the best possible world. So, I invite you to make an effort to connect yourself to nature. I have hope in our mercurial planet. As I connect with those around me and with nature, I can better understand Earth’s beauty. As living mirrors, let us all reflect Earth’s beauty, together.

Want to learn more about human interconnectedness? Check out the Interconnectedness module on My Best Self 101!!!

“We are all interconnected. Therefore, everything one does as an individual affects the whole.”

References

Howell, A. J., Dopko, R. L., Passmore, H., & Buro, K. (2011). Nature connectedness: Associations with well-being and mindfulness. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(2), 166–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.03.037

Holt-Lunstad, Julianne. (2021). The major health implications of social connection. Curr Dir Psychol Sci, 30(3), 251–259. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721421999630

Leibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm. (1714). “Monadology.” Philosophical Essays. Hackett Publishing Company. https://antilogicalism.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/leibniz.pdf

Leibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm. (1710). Theodicy. Anodos Books.

Zhang, J. W., Howell, R. T., & Iyer, R. (2014). Engagement with natural beauty moderates the positive relation between connectedness with nature and psychological well-being. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 38, 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2013.12.013